Senior Services

from our Members

- › Adult Day Care Services

- › Alzheimer's Facilities & Care

- › Assisted Living Facilities & Care

- › Care Manager / Geriatric Care

- › Elder Law

- › Eldercare Agencies & Associations

- › Geriatric Health Care Services

- › Guardian / Fiduciary Services

- › Home Care Services

- › Hospice Care

- › Medical Alert & Home Safety

- › Medical Equip & Assistive Tech

- › Nursing Home Facilities

- › Specialized Elder Care Services

- › More Eldercare Services

Books for Care Planning

Find books provided by the National Care Planning Council written to help the public plan for Long Term Care. Learn More...

Find books provided by the National Care Planning Council written to help the public plan for Long Term Care. Learn More...

Eldercare Articles

The NCPC publishes periodic articles under the title "Planning for Eldercare". Each article is written to help families recognize the need for long term care planning and to help implement that planning. All elderly people, regardless of current health, should have a long term care plan. Learn More...

The NCPC publishes periodic articles under the title "Planning for Eldercare". Each article is written to help families recognize the need for long term care planning and to help implement that planning. All elderly people, regardless of current health, should have a long term care plan. Learn More...

Join the NCPC

Become a member of the National Care Planning Council. Click here to learn about the benefits of membership.

Become a member of the National Care Planning Council. Click here to learn about the benefits of membership.

Guide to LTC Planning

From its inception, the goal of the National Care Planning Council has been to educate the public on the importance of planning for long term care. With that goal in mind, we have created the largest and most comprehensive source of long term care planning material available anywhere. This material -- "Guide to Long Term Care Planning" -- is free to the public for downloading and printing on all of our web sites. Learn More...

From its inception, the goal of the National Care Planning Council has been to educate the public on the importance of planning for long term care. With that goal in mind, we have created the largest and most comprehensive source of long term care planning material available anywhere. This material -- "Guide to Long Term Care Planning" -- is free to the public for downloading and printing on all of our web sites. Learn More...

Understanding Death

Cause of Death

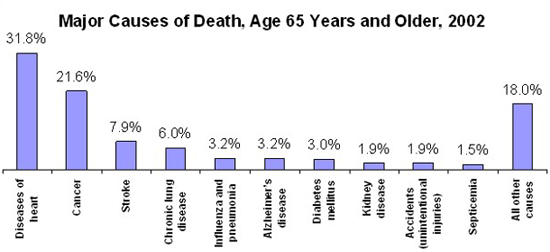

No one in this country dies from old age. In the mid-1950s, "old-age" was discontinued as a cause of death on all US death certificates. The assumption was that old age itself was not a disease but contributed to life-threatening disorders that were the ultimate reason for death. The chart below shows the major causes of death for Americans age 65 and older. About 53% of those deaths are due to cancer or heart disease. But note also the high incidence due to stroke and chronic lung diseases.

CDC, National Vital Statistics Report

Medical Care Prior to Death

In the first half of the 20th century most people who died had an accident or contracted a disease or had a physical disorder that quickly lead to death. Life-saving medical interventions such as sophisticated resuscitation, complicated surgeries, ventilators, feeding tubes and other life-support were rarely used or even available. Nowadays there is great emphasis on curing medical problems sometimes to the exclusion of recognizing that death might be a more welcome outcome.

Surveys indicate that older people are often more afraid of death than younger people. But for all Americans, young and old, there is a great fear of death and oftentimes family or those who are sick will go to great lengths to try procedures that may be ineffective in prolonging life.

According to the Dartmouth Atlas study on death:

"The quality of medical intervention is often more a matter of the quality of caring than the quality of curing, and never more so than when life nears its end. Yet medicine's focus is disproportionately on curing, or at least on the ability to keep patients alive with life-support systems and other medical interventions. This ability to intervene at the end of life has raised a host of medical and ethical issues for patients, physicians, and policy makers.

The Dartmouth Atlas project uncovered some startling differences in what happens to Americans during their last six months of life. In some parts of the country, nearly 50% of people are in the hospital at the time of death, rather than at home or in a nursing home or other non-hospital setting. In these areas, the likelihood of being admitted to an intensive care unit during the last six months of life is also higher than average - as is the likelihood of being admitted to an intensive care unit during the hospitalization at the time of death. In other parts of the country, the likelihood of a hospitalized death is far smaller, and people who are dying are much less likely to spend time in hospitals during their last six months of life.

The Atlas asked why this was so - why someone living in Miami was so much more likely to receive a great deal of high-tech, expensive medical services, while someone with the same condition who lived in Minneapolis received so much less. The answer appears to be that the capacity of the local health care system - the per-capita supply of hospital beds, doctors, and other forms of medical resources - has a dominating influence on what happens to people who are near death. Those who live in areas like Miami , where there are very high per capita supplies of hospital beds, specialists, and other resources, have one kind of end of life experience. Those who live in areas like Minneapolis or San Francisco , where acute care hospital resources are much more scarce, have very different kinds of deaths.

The question, then, is which is better? From the dying person's perspective, more is not necessarily a good thing - more visits to doctors for someone who is very sick can be stressful and exhausting. For many people a hospitalized death is something to be avoided if at all possible. From the perspective of the health care system, much of the care being given is futile, and accomplishes little. People who live in areas with very high utilization of hospital resources do not live longer than people who die in areas where utilization is lower - and if extension of life is not the goal of intervention, what is? From society's perspective, the cost of this kind of intervention is high, futile, and takes resources away from places where the money might be spent far more productively."

Deciding How and When to Stop Curing and Start Caring

Some people are content to leave decisions regarding their death in the hands of others. By doing so, they expose themselves to unnecessary and futile treatments as outlined above. They may experience numerous visits to the emergency room in the last stages of their life. And their dependency on others often results in great stress to family members when they lose their capacity and didn't make their last wishes known. Families are often forced to make decisions about life-support and treatment without knowing whether their loved one would have wanted these interventions.

Medical providers have come up against this situation many times and as a result there are written guidelines for doctors dealing with end-of-life issues. Here is a title listing of official positions taken by the American Medical Association on a number of end-of-life actions. Instructions on the handle each type of care have been deleted due to the length and detail. Of special interest are the instructions on "Optimal Use of Orders All Not to Intervene and Advance Directives." We include from the AMA the full instructions for this particular category

- Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders

- Futile Care

- Medical Futility in End-of-Life Care

- Quality of Life

- Withholding or Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Medical Treatment

- Optimal Use of Orders-Not-To-Intervene and Advance Directives

More rigorous efforts in advance care planning are required in order to tailor end-of-life care to the preferences of patients so that they can experience a satisfactory last chapter in their lives. There is need for better availability and tracking of advance directives, and more uniform adoption of form documents that can be honored in all states of the United States . The discouraging evidence of inadequate end-of-life decision-making indicates the necessity of several improvement strategies:

(1) Patients and physicians should make use of advisory as well as statutory documents. Advisory documents aim to accurately represent a patient's wishes and are legally binding under law. Statutory documents give physicians immunity from malpractice for following a patient's wishes. If a form is not available that combines the two, an advisory document should be appended to the state statutory form.

(2) Advisory documents should be based on validated worksheets, thus ensuring reasonable confidence that preferences for end-of-life treatment can be fairly and effectively elicited and recorded, and that they are applicable to medical decisions.

(3) Physicians should directly discuss the patient's preferences with the patient and the patient's proxy. These discussions should be held ahead of time wherever possible. The key steps of structuring a core discussion and of signing and recording the document in the medical record should not be delegated to a junior member of the health care team.

(4) Central repositories should be established so that completed advisory documents, state statutory documents, identification of a proxy, and identification of the primary physician can be obtained efficiently in emergency and urgent circumstances as well as routinely.

(5) Health care facilities should honor, and physicians use, a range of orders on the Doctor's Order Sheet to indicate patient wishes regarding avoidable treatments that might otherwise be given on an emergency basis or by a covering physician with less knowledge of the patient's wishes.

Treatment avoidance orders might include, along with a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order, some of the following:

- Full Comfort Care Only (FCCO);

- Do Not Intubate (DNI);

- Do Not Defibrillate (DND);

- Do Not Leave Home (DNLH);

- Do Not Transfer (DNTransfer);

- No Intravenous Lines (NIL);

- No Blood Draws (NBD);

- No Feeding Tube (NFT);

- No Vital Signs (NVS); and so forth.

One common new order, Do Not Treat (DNT), is specifically not included in this list, since it may unintentionally convey the message that no care should be given and the patient may lose the intense attention due to a dying person; FCCO serves the same purpose without the likely misinterpretation. As with DNR orders, these treatment avoidance orders should be revisited periodically to ensure their continued applicability. Active comfort care orders might include Allow Visitors Extended Hours (AVEH) and Inquire About Comfort (IAC) b.i.d. (twice daily).

Choosing Where to Die

Birth and death are consequences of life. They happen to every one of us. Where birth is often a joyous occasion, death is often a sad occasion. But it not need be. It is hard to let go of someone we are close to, but death also releases the loved one from pain, anxiety and unhappiness. For a caregiver, death is a welcome relief from years of sacrifice, stress and financial burden. And for those who believe in a life after death, a loved one has been released from a life of burden to a life of happiness.

Regardless of religious belief, the death of a loved one can often be a spiritual experience. But dying in the wrong setting can often lead to the departure of a loved one being an upsetting experience for the family. When a person expires, at peace in his or her own home, in a familiar setting and surrounded by loving family, that death can be an experience that the family cherishes forever. When a person dies in a hospital or nursing home amid the confusion of busy workers, tied to tubes and noisy machines and agitated by the lack of a familiar setting, that death may be remembered as an unsavory experience.

A recent survey by the End-of-Life Care Partnership, a Utah nonprofit end-of-life support group, sheds some additional light on the preference of Utahns where they would have chosen to die. A random phone survey of 150 survivors of recently deceased people was conducted. The deceased ranged in age from 23 to 100 but the mean age was 74 and over 75% of those who died were 65 or older. Over 80% of the respondents were spouses or children with the remainder having some other relationship to the deceased. The chart below indicates where the decedent's actually died.

| Place of Death | Home | Nursing Home | Hospital | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 37% | 33% | 28% | 2% |

About 54% of the subjects died where they wanted. This means the other half of the group were denied their preference of their place of death. Those who were 65 or younger more often died at home (55%) and 97% in this group preferred their home as a place of death. Of those over 80, 38% actually died in a nursing home whereas 76% of those over 80 wanted to die at home. Comparing their last desires to where the study group actually died indicates we are doing a very poor job in meeting the end-of-life wishes for terminally ill patients. The study also compared these results to national statistics reporting where death occurs and found that people from Utah died more frequently at home than people nationally. Also studies done nationally indicate that those who are currently living, predominantly would prefer to die in their homes.

The person who is dying can choose the setting if he or she wants. There is no reason to die in an institution unless there is little time to transport the person to a more familiar environment or unless a person specifically wants to die in a facility. A person who is cognizant always has complete control over the medical care he or she receives. If the person who is terminal cannot make such a decision, then the family can.

There is no reason for anyone to accept death in an environment not of his or her choosing. Too often people accept the situation and don't act aggressively in making their needs known. Too often for a loved one at home, who is dying, and who is in crisis from pain or other acute attack, calling 911 becomes the first option. The loved one in crisis is transported to a hospital where death may occur. With proper planning a crisis need not result in transportation to a hospital emergency room.

Palliative end-of-life care is now a commonly available alternative for people at home who are in the last stages of their life. This could be hospice or some other form of palliative care. A crisis under palliative care would result in a call to the attending nurse or doctor and based on prior arrangements or advice, the crisis would be handled without calling an ambulance. We recommend that all terminally ill patients and their family make planning for death, using palliative care, a routine part of the preparation for the end of life.

When Death Occurs

When a loved one dies at home, family or others who are there must often cope with the reality of the dying process. We recommend strongly that when a person is first considered being terminal, the doctor should be asked to order hospice care. We cannot stress enough how hospice care can help those involved get through a death at home or even in a care center. Oftentimes the family waits until a loved one is well along towards the end of life before hospice is considered.

Hospice is generally used for cancer patients because it is often easy to determine in advance whether a person will survive or not. If the cancer is not cured and continues to spread, death is usually inevitable. Whether that occurs in a matter of weeks or months is not important to the doctor prescribing hospice. The only requirement is the doctor must have a reasonable expectation that his patient cannot survive beyond six months. Sometimes hospice patients can receive care for years before they succumb.

For other medical conditions hospice may be just as appropriate but oftentimes the family fails to inquire or the family doctor simply doesn't consider it. Hospice should be considered for such conditions as congestive heart failure, advanced diabetes, advanced lung disease, advanced autoimmune disorders, advanced kidney disease and so on. Even in the absence of any medical condition, a person can still qualify for hospice if he or she is deteriorating rapidly and overall health is declining. Another condition often overlooked for hospice is advanced dementia or Alzheimer's disease.

Family often wait until a loved one starts shutting down before hospice is ordered. Or sometimes hospice is not even considered for Alzheimer's because doctors are so used to using palliative care only for cancer. If a loved one is not improving, family should always ask or even press for hospice. Remember not to wait until close to the end but order hospice at an earlier stage since it will help provide the necessary transition to the death of a loved one.

Why are we so adamant about using palliative care? Because these services focus on dying patients and will help the family get through not only the death but also give physical and spiritual comfort to the person dying as well as offering bereavement support after the death. We simply can't stress enough the importance of using this type of support when the end is near.

When a person is close to death, physical changes occur. Blood flow slows down and fingers and toes may start turning blue or black. Breathing is labored, there is a rattling at the back of the throat and the breathing process may even cease for long periods and then resume again. A loved one will be cold and it is important to provide blankets for warmth. A loved one may be confused or he or she may simply sleep a lot. Since these changes will be noticeable to the caregiver, a call to the hospice will receive immediate response with either a visit or instructions over the phone.

Remember hospice is on call 24 hours a day and the service is there to provide exactly this kind of support when death is imminent. Because of this support, the caregiver and other family members will be able to spend more quality time at the bedside of their loved one. Their fears for their loved one will be dealt with by a staff that can be relied on for knowing exactly what to do. Supportive services with the death of a loved one can make a huge difference in the way family handle the consequences of the death.

After death occurs, the hospice workers will also make arrangements for a funeral home to pick up the body. They will also help clean up any soiled bedding and talk to the attending physician about other follow-up, say an autopsy.